By SARAH BELLIS

News-Times intern

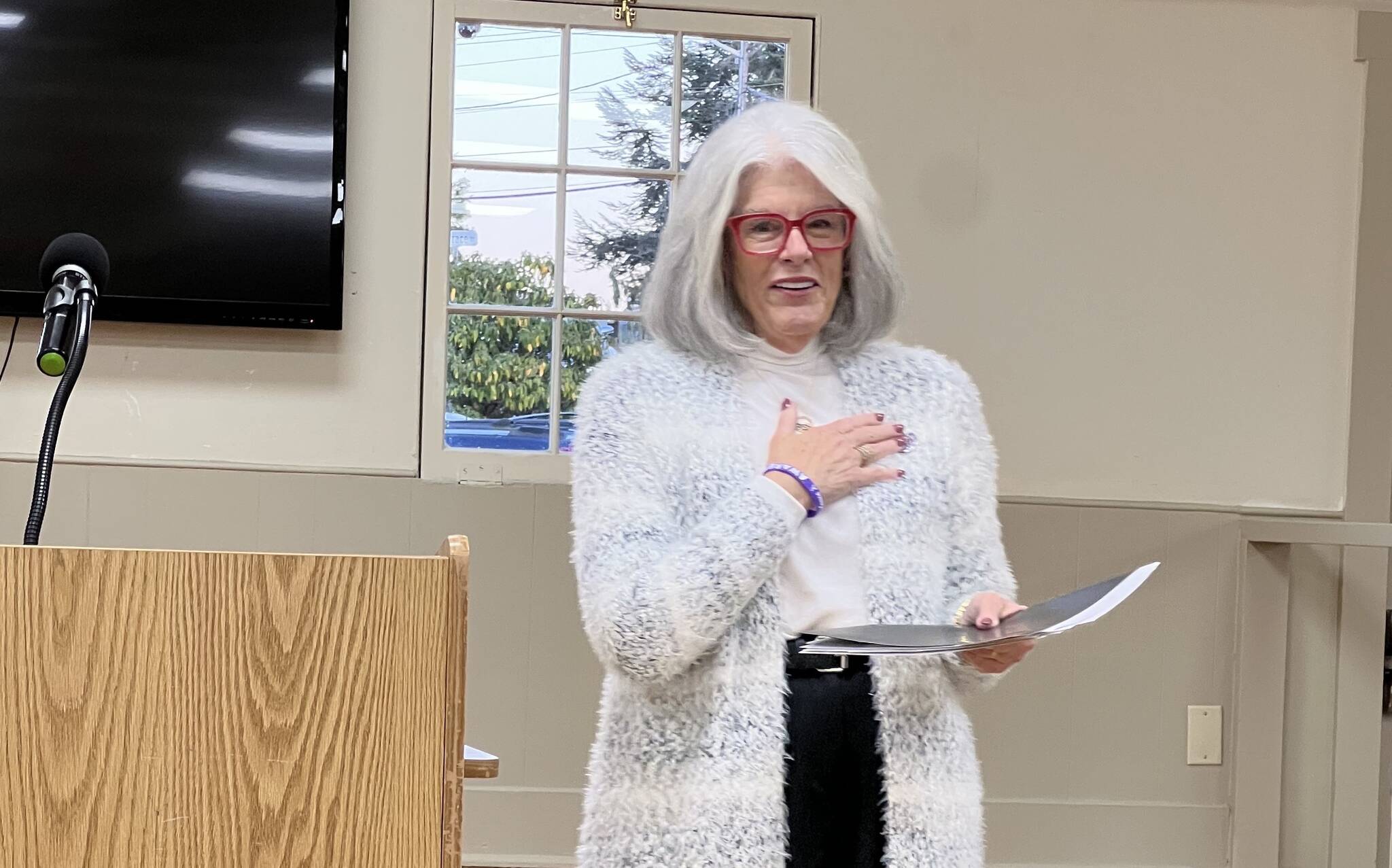

The room was quiet as author and domestic violence survivor Kathy Sechrist asked the audience at the Coupeville Recreation Hall to close their eyes and picture home. Not the idealized one — “children laughing, a partner’s embrace” — but when a heartbeat quickens and a hand pauses on the doorknob coming home.

“Your chest is tight, your stomach is in knots,” she said. “You brace yourself because you don’t know what’s waiting for you inside.”

For Sechrist, a former Whidbey Island resident, that vision wasn’t a writing prompt.

“What that vision was … was my reality,” she told the crowd. “Domestic violence doesn’t just hurt the body. It steals safety, robs identity and cages the spirit.”

The talk came at a time when Island County’s only domestic violence shelter is facing steep budget cuts — and when advocates say awareness, funding and safe spaces are more critical than ever. The evening event brought survivors, supporters and community members together to shed light on what domestic violence looks like this close to home — and how hope and healing begin with listening.

Sechrist’s first book, “Success is the Best Revenge,” details her abuse, while her second, “Sarah’s Redemption: A Journey of Courage, Resilience, and Hope,” draws from her healing experience. She spoke at an evening program in Coupeville that doubled as a community conversation and donation drive for Citizens Against Domestic and Sexual Abuse, known as CADA.

Before Sechrist took the mic, Andrea Downs, CADA’s executive director, thanked attendees for supporting survivors “who are rebuilding their lives with strength and dignity,” and spoke plainly about the organization’s finances.

“We lost almost a third of our budget this last year,” Downs said, noting reduced federal funding. “That really impacts the services our clients have access to — and it’s through your donations that we can fill some of the gaps.”

She described mothers and children arriving at Island County’s domestic violence shelter, sometimes on holidays, sometimes with nothing but a baby and a bag.

Sechrist’s keynote alternated between hard facts and survival. She spoke of childhood abuse, a mother who did not believe her and how those early betrayals “planted lies that take root deep in the heart.” As an adult on Whidbey Island, the pattern repeated — first as isolation and control, then as emotional and physical violence.

She recalled the night she dialed 911. Deputies separated her from her abuser and took him away.

“It’s not over when you think it’s over,” she said. “Victims will often still do all they can to help the abuser — until something happens and they can’t.” Healing, she emphasized, is “messy, jagged and slow.”

What changed everything was telling the truth.

“Shame cannot survive being spoken,” Sechrist said. “Writing my story was like breathing for the first time. Each page was a step in rebuilding myself.”

After Sechrist spoke, the quiet in the room broke into conversation. People asked how to help friends without making things worse, how to spot red flags earlier, whether calling the police is safe and how to support children who witness abuse.

“Listen. Believe them,” Sechrist said to one questioner. “You can help her make a plan — where to go, who to call, what to take. But she has to make the decision.”

Another attendee said her first shock wasn’t a punch — it was jealousy, restrictions on where she could go and who she could see.

“We need to teach young women to see the warning signs and run,” she said. Sechrist nodded and pointed to education resources and local workshops that spell out red flags: escalation, isolation, tracking, intimidation and financial control.

A longtime community member shared her husband’s story of surviving violence in childhood — twice taken out of school with a packed bag, crossing the country by bus with his mother and learning to be quiet, small and invisible. What saved him, she said, were adults who noticed: a teacher, a scout leader, a neighbor.

“When you reach out to a child, you don’t know what you’re giving them,” she said. “It could be a lifeline.”

Sechrist’s turning point came because a friend showed up unannounced.

“All it takes is someone to listen. Someone to notice,” she said, explaining that her friend spoke up after hearing a concern from someone else.

“You’re not at fault for asking the hard question,” Sechrist added. “You’re the helper. You give them the opportunity to be seen and heard.”

Downs described what dignity and safety look like in practice: clean rooms, fresh pajamas, fuzzy socks, stocked pantries, 24/7 staffing and a plan for what comes next — housing, legal help, school, work.

“We operate the shelter around the clock,” she said. “The little things matter. They remind people they are human and they are safe.”

But keeping that safety net intact is getting harder. With funding down, CADA is leaning on partnerships with the Housing Authority and Opportunity Council, plus community drives that provide basics and comfort items. Many in the audience also noted the dangers of domestic-violence calls and the importance of coordinated response and de-escalation.

“Awareness without action changes nothing,” Sechrist told the room. “If there are survivors here tonight, know this: Your story matters. Your voice matters. You are seen. You’re not alone.”

“Writing my story was like breathing for the first time,” she added. “Each page was a step in rebuilding myself.”

If you or someone you know needs help:

CADA (Citizens Against Domestic & Sexual Abuse) — Island County advocates, shelter, safety planning, legal & housing support. (Office in Coupeville; call for services and safety planning.) 1-800-215-5669.

National Domestic Violence Hotline: 1-800-799-7289.

In an emergency, call 911.

Connect with Sechrist, check out her website, kathysechrist.substack.com, or email her at kathy@kathysechrist.com.