Bill Ethridge has a quiet home on Front Street. Its manicured yard looks out over Penn Cove and as Bill and his wife, Mary, point out, it’s the only house on the block with a white picket fence.

Beautiful wooden floors stretch between the walls inside and photos of family memories are tucked away on shelves and countertops. A grocery list hangs on the fridge.

A visitor to Bill’s home could easily assume that his 80 plus years of life have been happy ones. It’s hard to imagine from his gentle steps and twinkling eyes that he’s ever known feelings of panic and terror.

The dining chair creaks as Bill sits down. A lawnmower hums in the sideyard as he adjusts his glasses and opens a book. Bill glances out the window, then turns his focus back to the kitchen.

“I’m going to tell you a story,” he says.

Bill joined the U.S. Army Air Corps when he was 19. After about two years of training, he had received his wings and was flying target missions during World War II.

On Oct. 6, 1944, Bill and nine other men were sent in a B-17 to bomb Berlin. On their way back to England they encountered several unexpected attacks.

“We were running out of gasoline because we were shot to pieces,” Bill says. “We could see we weren’t going to make it back.”

Bill and the men made an emergency landing in the North Sea and after a freezing night spent among the icebergs in an unstable boat slowly filling with water, they were spotted by a German aircraft and taken as prisoners.

After a brief stay on Noderney Island, Bill and the men would be sent to an interrogation center in Frankfurt, then camps in Sagan, Spremberg, Nurenberg, Munich and Moosburg, Germany.

Bill recalls walking 300 miles in the winter on the way to different sites and cooking pitiful food rations in makeshift tin can stoves. He saw his comrades commit suicide and watched his body shrink in hunger.

“We took it day by day,” Bill says. “That’s all we could do. We lost a lot of men.”

Bill would serve as a prisoner for seven months before he was rescued by U.S. Gen. George Patton and sent to Florida for a mandatory rest and relaxation period.

“I weighed over 160 pounds when I was shot down,” Bill says. “When Gen. Patton liberated our camp, I weighed 89 pounds. I came very close to dying.”

After settling back into life in the United States, Bill attended mandatory sessions with a psychologist who he said helped him work through his POW experience.

“It took a while to not dream about stuff at night,” Bill says.

When asked how he was able to keep his sanity through seven months of uncertainty and the torturous memories of recovery, Bill spills his secret: love.

Bill met his wife while she was a senior in high school during the beginning stages of his training in California, and they were married shortly before he was sent abroad.

“I think I had valid reasoning for trying to keep my brain in the right place,” he says. “We had a lot of suicides, but I felt if the guys really had an incentive to get back home, they would think twice about doing certain things.”

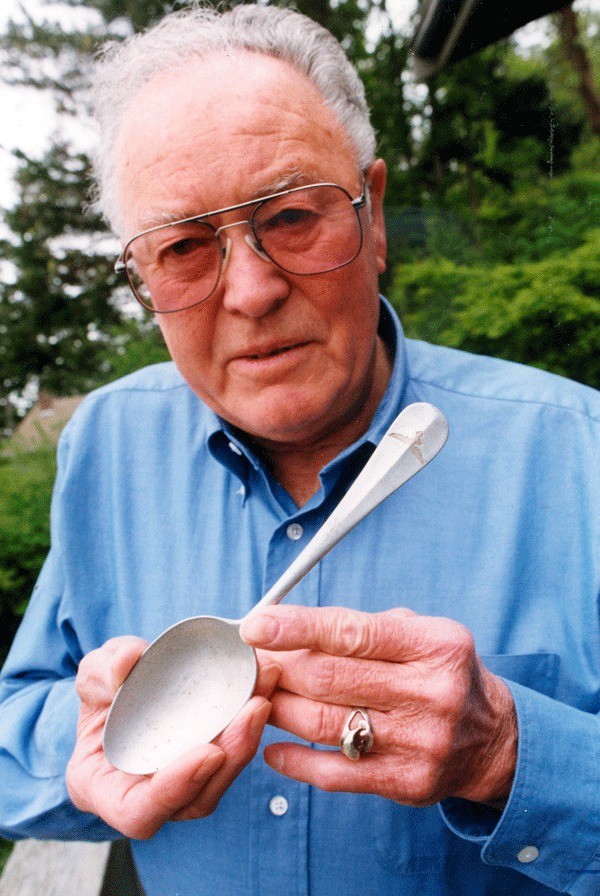

Now all that remains from Bill’s experience are the European map and bomber jackets that hang on a wall in a back room.

On Thursday Bill stood next to the prisoner of war flag at a ceremony in Coupeville, but he doesn’t say Veterans Day reminds him of his glory days as a flyer or of his bravery during history’s bloodiest period. Instead he says Nov. 11 always brings a certain tune to mind.

“Who wrote that song that goes, ‘when will we ever learn?’” Bill asks.

He straightens up the displaced papers and place mats on the kitchen table as he thinks, then continues, “When will we come up with a substitute for going to war? It’s so destructive. It’s so devastating. Why lose all these people?”