The most visited state park in Washington celebrates a century of recreation and conservation this year.

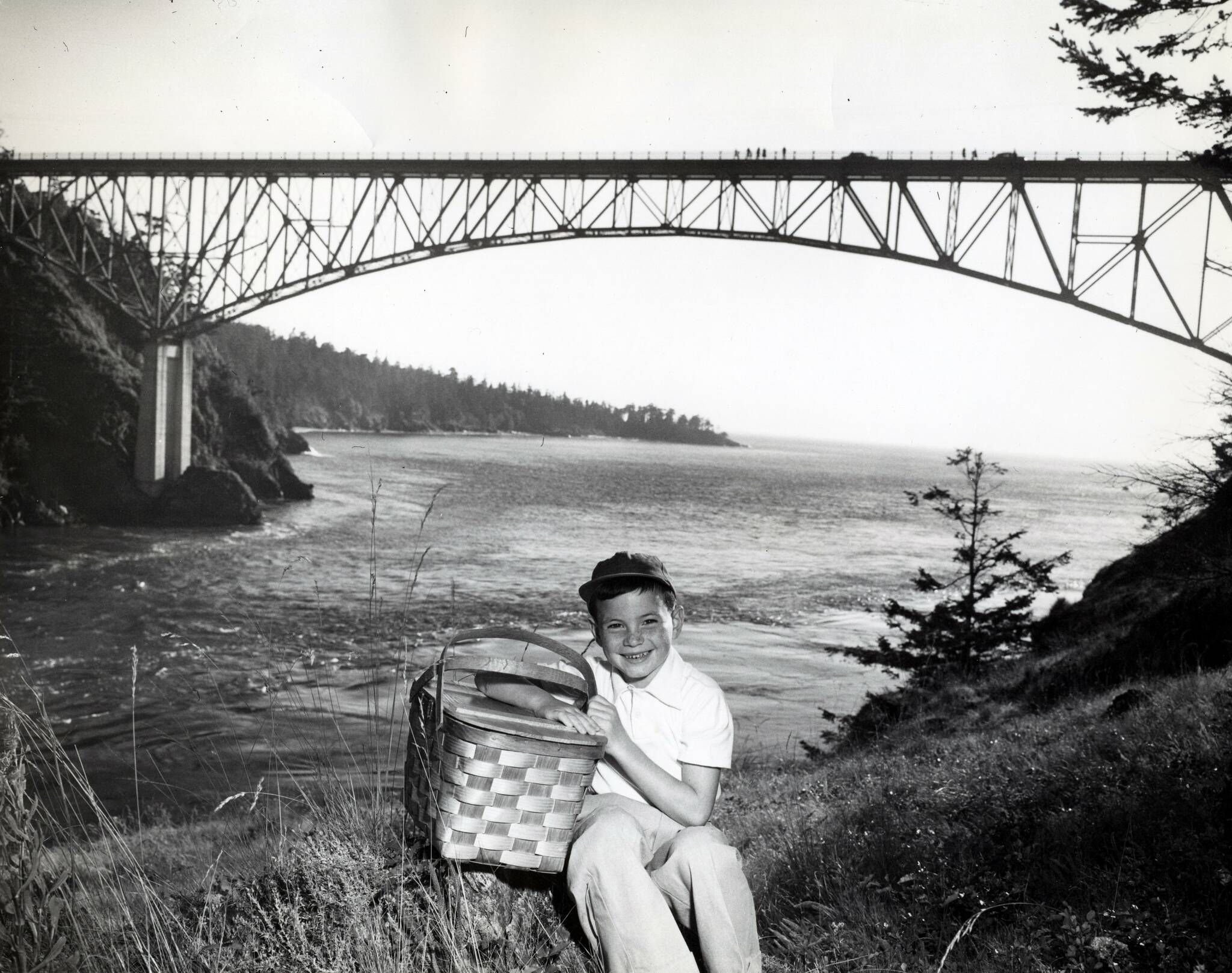

Deception Pass State Park spans nine islands in two counties, boasts around 40 miles of trails and welcomes more than three million visitors each year. The park is nestled around Deception Pass Bridge, a two-span structure that is one of the most photographed landmarks in the state.

The beloved park is an essential part of Whidbey Island’s economy and environment, and park staff and volunteers work relentlessly to ensure the area will remain a local treasure for more centuries to come.

HISTORY

Deception Pass State Park was founded on April 17, 1922. Prior to becoming a park, the land surrounding the pass on both the Whidbey and Fidalgo sides was owned by the U.S. military, with the purpose of protecting the passage from enemy ships.

With the advent of warplanes during World War I, however, the military decided it no longer needed the land and sold it to the recently created State Parks Committee at a low price. Shortly after, Deception Pass became one of Washington’s first official state parks.

When the Great Depression slammed the nation into economic hardship, Deception Pass State Park was one of the areas targeted by then-President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s Civilian Conservation Corps. The corps, one of many bodies created under Roosevelt’s New Deal, employed millions of young men in environmental projects.

The corps undertook park-related development work, such as trails and park structures, on both sides of the pass. Corps members also built the roads that would eventually lead to the bridge.

Around the same time, the Puget Construction Company began work on the bridge, which actually consists of the Deception Pass and Canoe Pass spans. Building from the outside in, workers completed the bridge in one year for less than $1 million. Adjusted for inflation, the cost of the bridge construction is equivalent to about $21 million today — roughly the same price it cost to repaint the bridges over the course of three years beginning in 2019, according to Deception Pass Area Manager Jason Armstrong.

The construction of the bridge was fairly controversial in its time, Armstrong said. The woman who ran the ferry between Fidalgo and Whidbey islands — the first female ship captain in the state — fought the installation, correctly predicting it would be detrimental to her business.

Eventually, “not having a bridge became such a barrier that the locals outweighed that, and the commerce outweighed that,” Armstrong said. The ferry only continued to operate for another year after the bridge opened.

When the bridges were completed, Civilian Conservation Corps members on Fidalgo Island had already finished the development in their part of the park and crossed to Whidbey Island to assist with the remaining work, Armstrong said. The corps built many of the 127 existing structures in the park today.

In the 1970s, many of the corps-built structures in the park were painted brown and dark green during a push for uniformity across state parks. Volunteers in the 1990s and early 2000s returned to strip the paint from the buildings, returning them to their original appearance as the park’s focus shifted toward heritage and historical preservation.

The park has grown in size over the years, expanding to include areas such as Hoypus Hill, which was scheduled to be clear cut until the park acquired it to protect its old growth forests, as well as Hope and Skagit islands.

TOURISM

Deception Pass is the most visited state park in Washington, and “it’s not even close,” Armstrong said. According to data from Washington State Parks, visits to Deception Pass and to state parks in general have been trending up since at least 2014.

Last year, almost 3.8 million people visited Deception Pass, and 1.2 million cars entered the park. According to Sherrye Wyatt, public relations manager at Whidbey and Camano Islands Tourism, Deception Pass kept up with some of the most popular destinations in the country last year; in 2021, 4.53 million went to the Grand Canyon, 3.29 million visited Yosemite and 2.72 million traveled to Olympic National Park.

Though Washington state residents make up around three quarters of the park’s annual visitors, Deception Pass draws tourists from all over the country and the world, including from just over the northern border. During non-COVID times, Armstrong said, Canadian residents often make up as much as 40% of Deception Pass campers. Wyatt added that she has known of visitors coming from places as widespread as Spain, France, South Korea, Germany and Australia.

The high visitation rates have significant economic returns for Whidbey Island. Armstrong pointed out that park visitors spend their money on ferry trips, meals from restaurants all over the island and stays in hotels, motels and AirBnbs.

The park even draws in film and commercial producers for its variety of wild locations, according to Wyatt.

“While it may not be possible to quantify the specific economic impact of the park to the county, we know it is a treasure,” she said. “According to a recent Dean Runyon report, direct travel spending on Whidbey and Camano Islands was $283 million in 2021. It is safe to assume that Deception Pass State Park contributed to that.”

ENVIRONMENT

The park contributes to more than just the local economy; it also has a significant impact on the local environment. Deception Pass is home to a variety of land and marine mammals, fish, birds, trees, flowers and more, including a number of threatened species that the park works to protect.

It also plays host to creatures who pop in for regular visits, such as a three-generation family of elephant seals that frequents the Bowman Bay area.

Park employees and volunteers have engaged in a number of conservation efforts throughout the park’s history.

Currently, volunteers are working toward the rehabilitation of the tide pools at Rosario Beach. The pools, which are home to snails, sea cucumbers, crabs, chitons and all sorts of other creatures, were almost entirely destroyed when they were trampled by a visiting group of students almost 30 years ago.

Today, park volunteers educate visitors about the organisms that live in the tide pools and help direct them along the proper paths for exploring. Park partners continually monitor the health of the tide pools.

Protected old growth forests fill the park. The oldest tree in the park is over 900 years old, Armstrong said, adding that it was being “loved to death” by park visitors who could not resist climbing or hanging up a hammock in its many gnarled limbs. Park personnel have put up a fence around the tree to encourage visitors to love it from a distance.

Volunteers recently carried materials by hand to the top of Goose Rock to build a fence that would protect wildflowers and succulents from being trampled by hikers. Goose Rock is the highest point on Whidbey Island, and around 80 volunteers and nine staff members hauled 430 split rails to its peak for the fence construction.

PARK TODAY

Deception Pass employs 14 full-time staff year round, a number that balloons to around 30 staff during peak season, Armstrong said. But the park’s many programs and recreational opportunities would not be able to function without the help of a hardworking corps of volunteers.

Volunteering takes several forms at the park. Many volunteers, such as the Beach Naturalists who help protect the Rosario tide pools, are organized through the Deception Pass Park Foundation, the nonprofit fundraising arm of the park. The foundation organizes volunteers to clean the campgrounds, run the park store, build picnic tables and assist in ongoing park maintenance projects.

Beach Naturalist volunteers make up just one part of the park’s interpretation program. Led by interpretive specialist Joy Kacoroski, the program educates park visitors, including student groups, about the park’s history and ecology through hands-on experiences.

According to Nan Maysen, a Beach Naturalist volunteer and former executive director of Sound Water Stewards, interpretive programming is all about helping the public understand the value of the park and the best ways to respect and care for it.

“The more that people understand, the more fascinating it is for them, so the best part for me is being that link,” she said.

The park’s many annual visitors enjoy a variety of recreational and community activities throughout the year. People come to Deception Pass to hike, swim, kayak, windsurf, camp, take a boat tour, watch for whales or picnic on the beach.

While some of the most iconic locations, such as the bridges or West Beach, receive a lot of attention, visitors might enjoy getting off the beaten path to explore some of the park’s hidden gems, such as Hoypus Hill or the Dugualla Bay Preserve, Armstrong said.

Deception Pass also sponsors a number of arts-based programs. The annual American Roots concert series brings musicians to the park’s amphitheater for weekly performances. This summer, the park will also bring on two artists in residence, a painter and photographer, who will live in a cabin on Ben Ure Island and teach art classes during July and August.