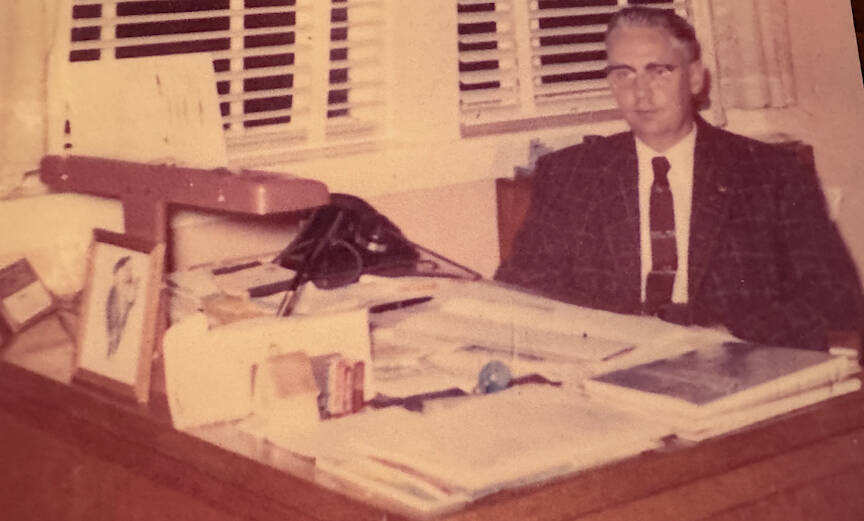

When Dr. Paul Bishop came to Coupeville in 1949 and became the town’s only doctor with an office on Front Street in what had once been the Elkhorn Saloon, health care on Whidbey Island was very different than it is today.

There was no hospital; Whidbey General Hospital didn’t open until 1970. There were not many other doctors on the entire island; Oak Harbor had a couple, Langley and Freeland had a couple more. And the number of potential patients then wasn’t huge. The population of Island County was just over 11,000, according to the 1950 census; by 2020, it had swelled to more than 86,000.

Dr. Bishop was born on a farm in Garfield, Washington, near the border of Idaho. He graduated from Washington State University and then entered the Army during World War II. The Army paid for his medical education at Portland Medical School, and he remained in the Army until the early months of the Korean War.

He moved to Coupeville when he read an advertisement posted by Wilbur Sherman and several other prominent residents seeking a new town doctor to replace the one who recently moved away. A town without a doctor on Whidbey at that time could be in serious trouble; a Coupevillean just wouldn’t visit a doctor in Oak Harbor or Langley, and vice versa.

Dr. Bishop quickly became a beloved figure in Coupeville. “He was our Dr. Welby,” as one resident recalled, referring to a kindly doctor in a popular 1970s television show. Paul Bishop and his wife Betty had 10 children — nine boys and one girl. Five still live in the area: Paul; Lyall, a retired pediatrician; Malcolm; Wilbur, a farmer on Ebey’s Prairie; and Robert, who served as Island County coroner for a number of years.

The family bought some acreage with an orchard near Sherman and Black roads, built a house and barn and started their own small farm. The old barn still stands on the property, which continues to be owned by some family members.

Dr. Bishop cut a wide swath through the community — and not always just because he was a good doctor. He also loved powerful cars; he bought a Chrysler 500 in the mid-1950s and was known for driving very fast everywhere, sometimes upwards of 100 mph. He even installed aircraft seat belts in that car for his own safety, long before seat belts were mandated in all cars.

He also owned his own single-engine airplane and sometimes joked about flying emergency patients to a hospital in Everett.

Furthering his reputation and legacy was the tireless work his sons did at his medical office. They stoked the waiting room stove with driftwood, painted the building several times, helped add on a room and even helped their dad set the broken bones in some patients.

He also talked continuously about the need to build a hospital on Whidbey Island — a dream that had been active for decades and grew more intense after World War II, as veterans returned home having seen hospitals all over the nation and the world. He spoke to a number of women’s groups who were raising funds to build a hospital; they evolved into guilds that were active for decades after the hospital finally opened. One of those guilds, active until about 15 years ago, was named the Dr. Paul Bishop Guild, in his honor. And Dr. Bishop was often cited as one of the driving forces that got the hospital built.

In addition, he was known for working impossibly long hours. He might see 15 or more patients every day in his office, starting at 8 a.m. Then he often made house calls after the office closed and sometimes didn’t get home until 11 p.m. or later.

But the era of Coupeville’s beloved Dr. Bishop came to a sudden and tragic end early on the morning of March 3, 1962, when he died at home of a heart attack at the age of only 47. His widow remained in Coupeville with their children until she died in 1968.

In the intervening years, with the huge increase in population and dozens of new physicians and nurses, the memory of how things used to be and what it was like before Whidbey had a hospital has faded. His office on Front Street is now an antiques shop. If you look carefully, Dr. Bishop gets a brief, one-sentence mention on the hospital’s history wall.

Before the hospital built its addition several years ago, a portrait of Dr. Bishop used to hang on a wall, painted by a local artist and donated to the hospital by the Bishop family. It was taken down during the construction and today no one seems to know where it is. The hospital has promised to keep looking.

Judy Bishop, wife of Lyall Bishop, would love to see the portrait back up on a hospital wall. “He did so much for the town while he was here; it shouldn’t be forgotten,” she said.

Indeed, a legacy this rich needs to be remembered.

Harry Anderson is a retired journalist who worked for the Los Angeles Times and now lives on Central Whidbey.