West Nile virus isn’t far, as the crow flies, from Island County.

Earlier this month, officials in Pend Oreille County in Eastern Washington confirmed the exotic virus’ presence in a dead raven. But even before the virus was discovered in the state, people had been preparing for its arrival.

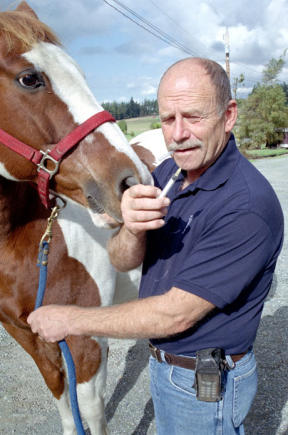

Oak Harbor veterinarian Kent Freer and his associate, Dr. Robert Moody, have vaccinated more than 100 horses since last August.

“West Nile is a terrible death for horses to suffer,” said Marie Freer, the vet’s office manager. “This year we vaccinated our horses.” Marie Freer also said, “West Nile is traveling much faster than other diseases. It’s phenomenal how fast it’s coming.”

Birds in the corvid family — jays, crows, magpies and ravens — are the most commonly infected birds. U.S. Geological Survey’s Web site lists more than 110 species of birds — from hummingbirds to eagles — known to carry West Nile.

The virus is transmitted by mosquitoes primarily to birds and horses. Humans can contract the disease but despite media attention, few people die from West Nile infection.

The USDA has given West Nile vaccine a “conditional” status, meaning not all the vaccine’s possible complications are known. The vaccine is given in three doses: two shots 2 to 3 weeks apart and a booster in the spring before mosquito season starts. Conditional status means only veterinarians can administer the doses, so the cost is a little greater than other vaccines. However, Freer has been waiving a call charge if horse owners get 10 horses at one location. “We’re trying to keep the cost down so it’s not super-expensive since people can’t get the vaccine from a feed store,” Marie Freer said.

She added, “USDA is using real common sense in letting the vaccine out to meet an emergency situation. We haven’t seen any reactions or complications from any horses.”

Amy Hauser, 4-H leader for Coupeville Cossacks, said that at the group’s last meeting of the year, an announcement was made about West Nile and the recommendations for horses to be inoculated. “We can’t make people do things,” Hauser said. “Some people vaccinate for everything and some people do only the minimum.”

Hauser said she has asked veterinarians questions about West Nile. “I’m not worried about human health. No one in my family is elderly, infirm or at risk for West Nile,” she said. But her daughter’s horses have been vaccinated. “When we have our next meeting, we’ll be telling people West Nile is here,” Hauser added.

Wildlife biologist Matt Klope has been picking up dead birds in Island County for years but has yet to deal with West Nile. “I bag, tag and freeze dead birds. Every six months or so I send an ice chest to the Smithsonian for its collections,” he said.

Klope is the program coordinator for the Department of the Navy’s Bird/Animal Aircraft Strike Hazard program. Every bird that’s found dead on a flightline on any base worldwide is picked up and processed. While Klope isn’t too worried about West Nile, he does have some questions. “I’m only on the very edge of West Nile. I’ve talked to Natural Resources in Washington, D.C.,” he said. “I’ve asked for guidance on what a bird that had West Nile might look like. Hopefully, something will get out to people in the field that we can use.”

According to “Shorelines,” Whidbey Aubudon Society’s newsletter, Island County Health Department has been collecting and testing dead crows and ravens since June. The health department asks that no dead birds be brought to them but anyone who finds a suspicious bird may call the health department at 679-7350.

Klope does have this advice for anyone who picks up a dead bird: “Wear gloves. Birds have lots of parasites.”

It’s inevitable that a crow or some other bird will bring West Nile Virus to Whidbey Island. However, when it arrives, many of the island’s horses will be ready for it.