As the entire nation hunkers down, dons face masks and avoids others to fight COVID-19, here’s a look back at how this community fought the Spanish Flu pandemic of 1918, compiled from Whidbey News-Times archives.

There is definitely an echo of what’s happening today.

At the request of state and county health officials, Oak Harbor Mayor Frank Stallman signed an order closing “churches, schools, pool rooms, lodges, dance halls, card parties, Red Cross meetings, social gatherings and all public gatherings” on Oct. 23, 1918.

Two weeks later, the health officer in Oak Harbor received an order from the state setting forth rules for people to make masks from “not less than six layers of surgical gauze” and requiring that they be worn in public places.

The two competing newspapers on Whidbey Island, the Oak Harbor News and Island County Times, recorded the impact that the Spanish Flu was having on Whidbey 102 years ago.

The nation had been fighting World War I for almost two years, and the newspapers that year were dominated by stories about Whidbey “boys” who were either doing well or had been killed fighting in Europe. Letters from soldiers overseas were regularly published, as were stories about war crimes committed by the “Huns.”

One big story that year was about a teacher who was charged with disloyalty for lackluster patriotic instruction and lack of support for the Red Cross. After a trial before a state school authority, he was stripped of this teaching credentials. His wife was later stripped of hers as well.

A letter from the county’s health officer, published Oct. 1 in the Island County Times, was the first story about the Spanish Flu. This was at the same time the second wave of the flu was spreading through Seattle.

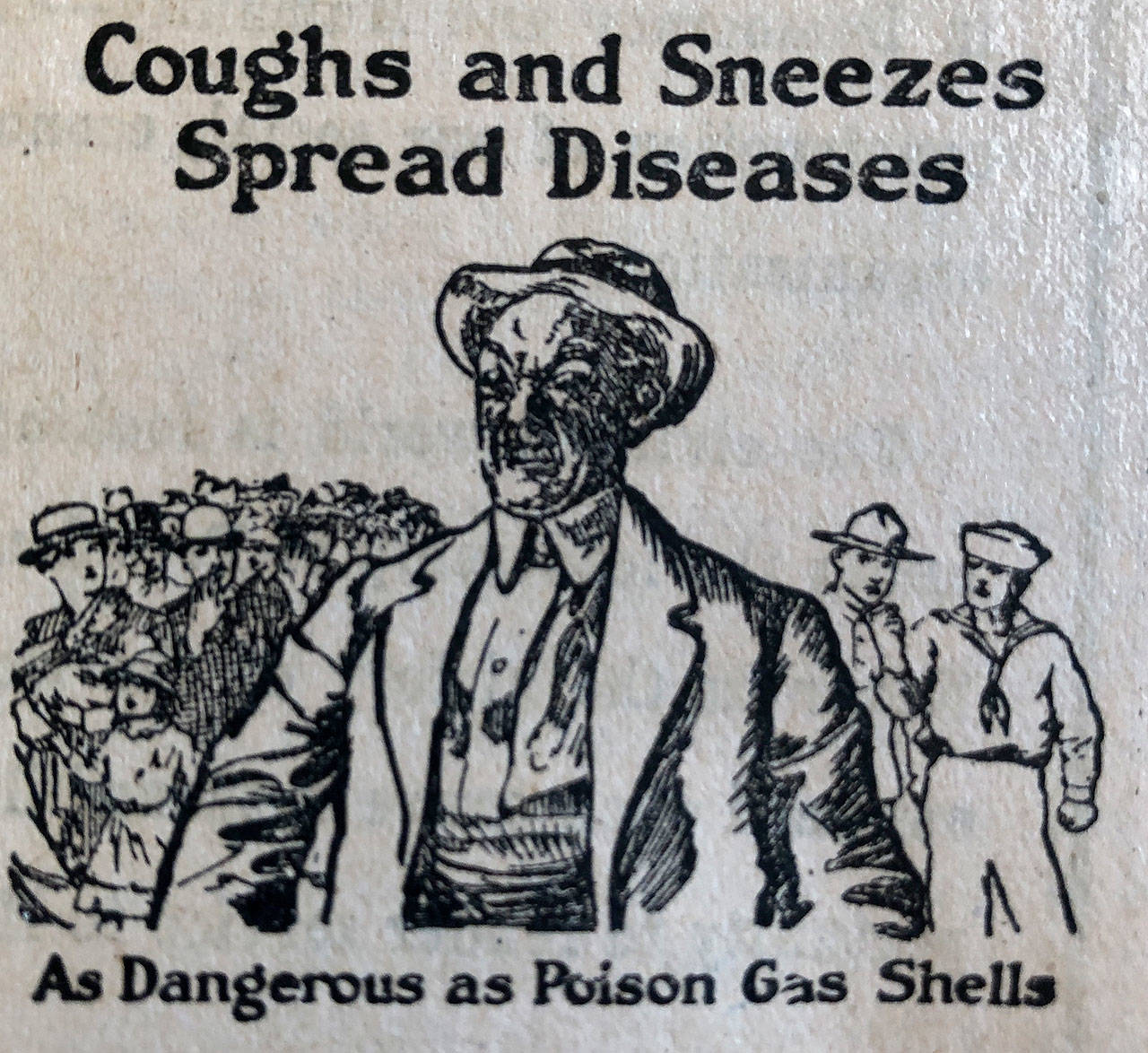

Health Officer K.J. O’Neill wrote that the illness was spreading “in a manner that was altogether mysterious and disconcerting,” and he lamented “the deplorably low standard of public conduct that prevails in the manner of coughing, sneezing and spitting without use of a handkerchief.”

Ten days later, the Oak Harbor News reported that the only case of Spanish Flu in the Oak Harbor vicinity was contracted by Sidney Jongsma, who had returned from a visit to Seattle.

“To keep one’s system in the best condition to resist infection,” the story said, “sleep in the fresh air, bathe frequently and keep the elimination organs active.”

The newspapers continued to report on many meetings and public gatherings until the mayor’s Oct. 23 order banning them.

On Oct. 25, the Island County Times reported in two front-page stories that “Death Takes Dr. K.J. O’Neill” and “Former Coupeville Girl Dies.” Both were victims of influenza.

“Seldom has a death cast so much universal gloom and sadness over this entire community,” the story of O’Neill stated, explaining that he died of pneumonia “following a siege of the dreaded Spanish influenza.”

The war ended on Nov. 11 with the signing of the Armistice. The next day, the county’s new acting health officer, J.R. Persons (who succeeded O’Neill) signed a notice revoking the order forbidding public gatherings.

The stories about influenza decreased precipitously until the end of December, when new items started reappearing. Beryl Dremolski, a Coupeville teenager, died from the Spanish Flu on Christmas Day. Doris Sherman, a fourth grader in Coupeville, died from the flu on Dec. 17. Her siblings were also infected but survived.

Over the next few months, the short “news notes” about people’s personal lives and activities in both papers started recounting dozens of residents who were sick with the flu. Yet the newspapers didn’t describe any measures that the community took to contain the infection for months.

Notes about Oak Harbor in the Jan. 10 edition of the Island County Times, for example, described several people who were sick or recovering from influenza. The family of Will Dougliss had suffered from the illness during the previous week but was recovering.

Nonetheless, Councilman H. T. Hill celebrated his birthday and threw his annual “stag party” for some of his friends. “A good social time was had by all,” the note stated.

By April 11, 1919, the Oak Harbor News reported that there were nearly 200 influenza cases in the city and surrounding neighborhoods alone. Public schools and churches had again been closed. Yet, in the next issue, a front-page story — with a much larger headline — told of a “mass meeting” that was planned to discuss possible county ownership of the Deception Pass ferry.

The April 11 story about the flu said there were “quite a number of families” in which every member was infected and that the island was handicapped by a lack of nurses to care for them. Another story said 29-year-old Herman Eerkes was “the first victim of the influenza which is now spreading so rapidly over the north end of Whidbey Island.”

A story in the edition offered some medical advice from a New Mexico health official that likely did not help matters. He advised that those sick with the flu be given capsules containing ammonia carbonate, quinine, strychnine and hydriodic acid.

Stories about Spanish Flu disappeared from the pages of the newspapers in the weeks that followed.

The local Spanish Flu outbreak reported in the Whidbey newspapers in 1918-19 corresponds with what is now understood as the second and third waves of that pandemic, which was the most severe in U.S. history, according to the Centers for Disease Control.

The Spanish Flu pandemic peaked with the second wave, which caused the most deaths across the nation.