When Coupeville resident Anita Burdette-Dragoo began volunteering at the lighthouse at Fort Casey, she noticed the lack of human interest stories among the voluminous historical information, so she set to find one.

She eventually wrote a book about one decorated World War I soldier, Capt. Mathew L. English from Fort Casey, who gained the admiration of Col. George S. Patton for his service.

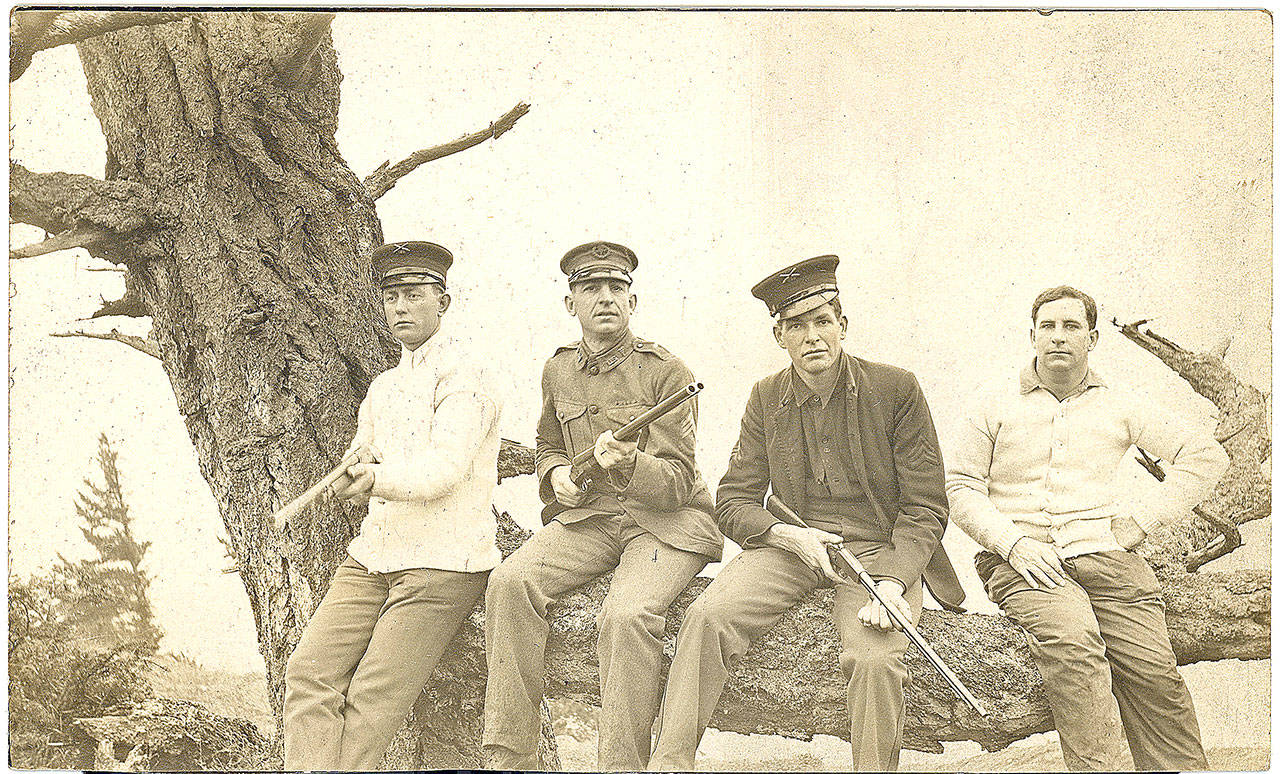

Burdette-Dragoo, a retired teacher for the Department of Defense for children from military families in classrooms all over the world, was given a binder by the executive director of the Admiralty Head Lighthouse at Fort Casey and told to find a human interest story. It included photographs of items from a World War I soldier’s foot locker belonging to English that had been donated to the park by his family.

Steven Kobylk, a local military historian and Whidbey Field Representative for the Coast Defense Study Group, photographed everything inside the trunk and offered to let Burdette-Dragoo see the items for herself. In it she found English’s gas mask, cap, an item worn on his collar, photographs and some letters.

“Just having hands on those things — it was just amazing,” Burdette-Dragoo said.

Two of the letters were from Patton and his wife to English’s wife, Mary Alice.

The famed military leader expressed his personal sympathies for Mrs. English. English was serving under Patton at the time he was killed.

“In my own experience I have never seen, and I have yet to hear of a more heroic exhibition of devotion to duty and scorn of death,” Patton wrote of English.

Burdette-Dragoo knew she had to find out more about the WWI soldier.

“I thought, well, this guy has got a little bit of history. He’s not just your ordinary soldier.”

There was also a newspaper clipping of a poem Patton had written about English’s life and death while he was recuperating from an injury. Patton wrote it on Nov. 11, 1918 after peace had been signed, which would later become Veterans Day. Burdette-Dragoo said the poem was released after Patton’s death in 1945 in a Texas newspaper.

“The thing that intrigued me the most was the poem that George Patton had written,” she said.

She began researching. The best source that helped her learn about English’s life was an obituary in the Island County Times, the predecessor to the Whidbey News-Times. English’s wife was the daughter of the newspaper’s owner and editor, William T. Howard.

The obituary explained where English was from and how he got to Fort Casey. Burdette-Dragoo learned he was from a small town in Georgia that about the size of Coupeville. She contacted a teacher at a local high school on a whim, hoping he might know something and he responded, saying that English’s family had owned a mill.

English was also mentioned before he entered the war. On the front page of the Feb. 26, 1915 of the Times, he reportedly brought the first Buick automobile to Island County.

English arrived at Fort Casey in 1904 and lived in Central Whidbey until he was commissioned as a second lieutenant in June 1917 and sent to Europe. He was among the first men to be a part of the American Expeditionary Forces Tank Corps, and was promoted to the rank of captain serving in the 344th Tank Battalion, Tank Corps under Patton.

English received two Distinguished Service Crosses for his service in the Tank Corps, the second-highest honor for a member of the Army. Patton recommended English for his first honor for dismounting from a tank and supervising the cutting of a passage under heavy machine gun fire through three hostile trenches, according to Burdette-Dragoo’ book.

English was awarded his second honor posthumously. He had left his tank under heavy machine gun and artillery fire to conduct reconnaissance and was killed on Oct. 4, 1918.

One of the more personal discoveries Burdette-Dragoo found came from a collection of letters from a soldier, Lt. Harvey Harris, that his family published. In it, the soldier recounts the quiet night before the men were to “go over the top” in battle, she said. In a letter to his parents, Harris recalled the men reading letters from home, and someone began playing a salvaged piano while another person sang.

He also wrote “Capt. English and Lt. (Robert C.) Llewelyn — both killed the next morning — were most optimistic. They’d made reconnaissance that afternoon.”

Burdette-Dragoo was stunned at the find.

“And I thought, ‘Wow — this is what Captain English felt the night before he was killed in battle. What are my odds?’”

She had also learned that English had written to his wife that he hoped to be home by Christmas that year, potentially sent back the states to become a trainer for future tank corps.

“That got me more than anything,” she said.

Burdette-Dragoo self-published, “A Hero for All Time: A Decorated Solider of World War I, Mathew L. English from Fort Casey, Washington” about English’s life and service in 2016. It can be found at the Island County Museum and Amazon, although she said it may be in a local book store soon.

She was surprised by how much information she found from seemingly small clues. Her advice to aspiring writers is to follow any lead.

“Follow every trail. Work outside the box for thinking of things that might be related, and talk it up to people you meet,” she said.

English’s footlocker has been moved to a state facility with controlled conditions for safekeeping

“We were hoping it would have been on display at the park. It would be nice for other people to see them,” she said.

Kobylk said he was impressed by Burdette-Dragoo’s research into a local hero.

“The discovery through Anita’s book (is) the true story of a true, humble, American hero and his sacrifice to his country,” Kobylk said. “His story is far more reaching on an international level then just our island.”

Written by Col. George S. Patton, printed in “A Hero for All Time: A Decorated Solider of World War I, Mathew L. English from Fort Casey, Washington”

The war is over and we pass

To pleasure after pain,

Except for few who ne’er shall see

Their native land again

*

To one of these my memory turns,

Noblest of the slain;

To Captain English of the tanks

Who never shall return.

*

Yet should some future war exact

Of me the final debt,

My fondest wish would be to tread

the path which he has set.

*

For faithful unto God and man

And to his duty true,

He died to live forever

In the hearts of those he knew.

*

Death found in him no faltering

But, faithful to the last,

He smiled in the face of fate

And mocked him as he passed.

*

No, death to him was no defeat

But victory sublime;

The grave promoted him to be